Some sort of rebound was almost inevitable given the team’s talent, but the complete change in the team’s attitude under the Spaniard has been nothing short of remarkable.

Ever since the club acquired the unwanted “Neverkusen” moniker following three runners-up spots in 2002, Bayer had been a byword for underachievement and lack of resilience. Now though, they are coming back from a late goal away to serial champions Bayern to score an even later equaliser and generally play with a swagger that befits the most balanced, confident team in the league.Sporting director Simon Rolfes makes no effort to underplay the manager’s role in this transformation. “There’s a seriousness and maturity in our football that reflects Xabi as a person,” the 41-year-old tells The Athletic. “He’s a natural competitor and winner. He’s instilled a battle-hardened attitude and a fighting spirit in the side.”

Rolfes points to February’s knockout-stage win against Monaco in the Europa League as a key game in lifting spirits last season. “We were the better team in the first leg at home but lost 3-2 because of two late goals.“

In Monaco, we were again the better team and should have won it in 90 minutes. But we had to go into extra time and then to penalties — after we had missed the last seven spot kicks in a row. It was all set up for another unlucky finish. Things looked like they were going against us all season. But we scored all five and won! That was an important moment for the team and all of us.”

Bayer went on to narrowly lose against Jose Mourinho’s Roma in the semi-final.

Tactically, Alonso has drawn from many of the different ideas he encountered playing under Pep Guardiola, Jose Mourinho, Carlo Ancelotti and Rafael Benitez. His first move was to stabilise the defence, playing counter-attacking football. Once they were more solid out of possession, Alonso put his attention to improving Leverkusen’s quality on the ball. They have taken another big step forward this year, becoming more and more watchable, and they are now playing the best football in Germany.“

Xabi is not a dogmatic manager,” Rolfe says. “When necessary, the team know how to defend or be pragmatic in certain situations, it’s not always the beautiful build-up from the back. Finding a way to win is what matters to him, more than anything.”

However, there is a sense that Alonso’s philosophy is firmly rooted in his development at his boyhood club, Real Sociedad. He had his first playing and managerial opportunities at a club that has an emphasis on producing technically gifted players to play controlled, possession-based football.

He took La Real’s B team to promotion to the Spanish second tier for the first time in 60 years. Although they were relegated at the end of that campaign, there are caveats, namely his youthful squad, which had an average age of 21.4 years). His inexperienced team still topped 70 per cent possession in seven separate games.

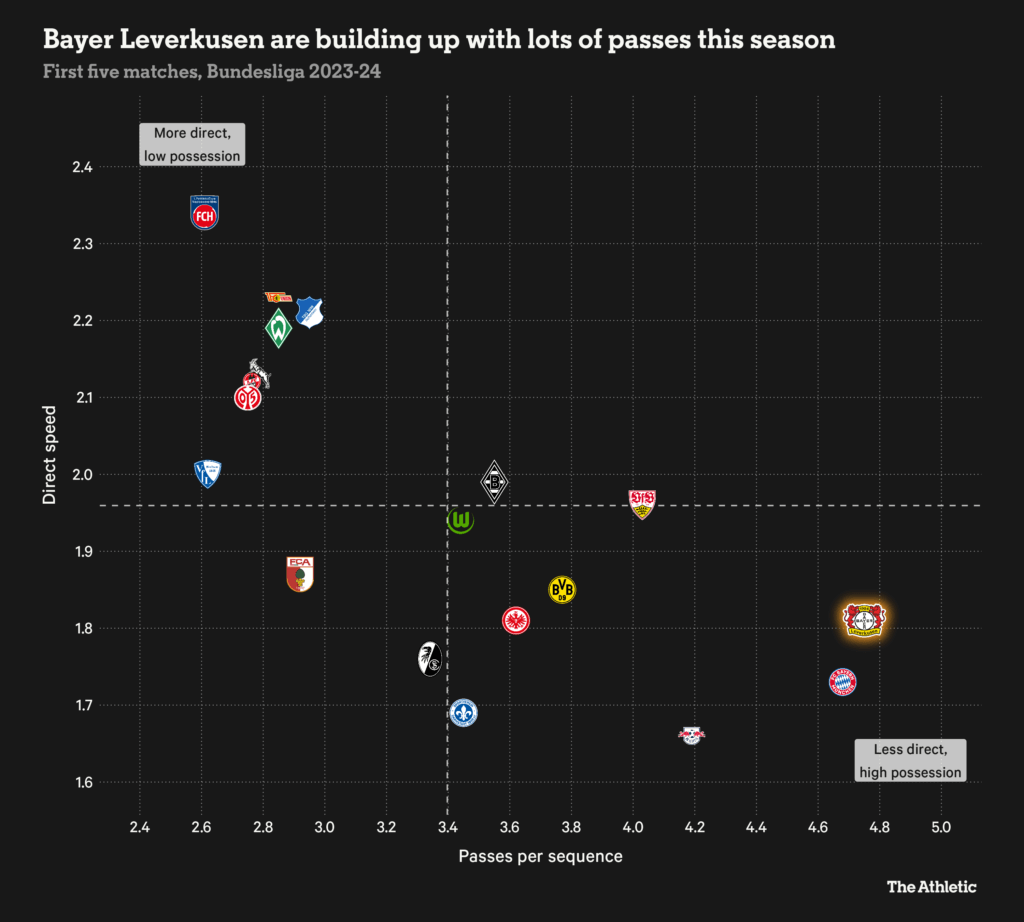

At Leverkusen, their steady improvement has coincided with the increased control in their build-up across the last calendar year, with their blistering start to the season built on pass-heavy attacking moves.

As the scatterplot below illustrates, no side have averaged more passes per sequence throughout the opening five games. They have even more than Bayern. Leverkusen’s slightly higher ‘direct speed’ (how fast the ball moved upfield) suggests that they can be quick and incisive when the space opens up too.

Summer recruitment has also accelerated Leverkusen’s progress, with tactically versatile players allowing for a new system.

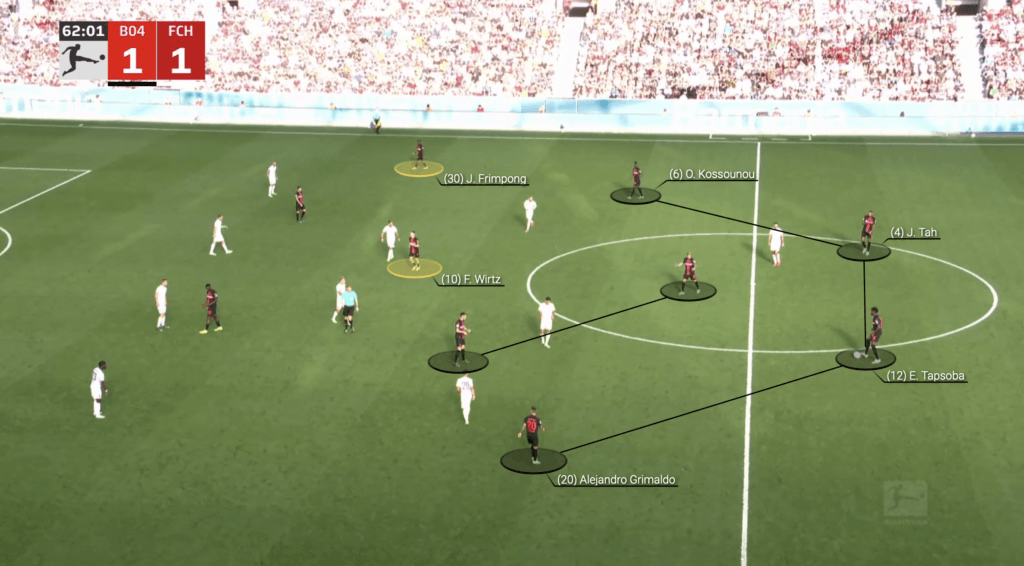

Wing-back Alejandro Grimaldo has given Alonso an attacking threat down the left-hand side — after generating 12.7 expected assists (a measurement of the quality of chances a player creates) last season at Benfica, a figure that only five players in Europe’s top-seven leagues could better — along with defensive solidity, which allows Leverkusen to shift into a solid back-four shape in the build-up.

Centre-backs Edmond Tapsoba, Jonathan Tah and Odilon Kossounou all move over, allowing the dangerous Jeremie Frimpong to push on with more freedom.

In the middle, the experienced Jonas Hofmann is a talented technician who can combine with Frimpong and cover defensively for his live-wire team-mate, while Granit Xhaka has reinforced a solid double-pivot, encouraging the creative presence of Florian Wirtz to roam across the attacking third in search of the ball, as below.

Leverkusen scored their second goal against Heidenheim with this exact structure at the weekend, as Hofmann darted in behind to receive a perfect through pass from Exequiel Palacios.

There’s also the relentless Victor Boniface, who has averaged an incredible 7.6 shots per 90 minutes since joining the Bundesliga, to go alongside his explosive off-the-ball running. Leverkusen are a potent attacking force.

“Having a deep theoretical understanding of football and a superstar aura from winning everything as a player is a ridiculously powerful combination for a manager,” one senior Bayer official tells The Athletic on condition of anonymity, maintained to protect relationships. “He’s done it all but he has the work ethic and humility of a total novice.” Alonso is the first one in and last one out every day, brooding over tactical details for hours on end.

An employee who saw him address the annual staff meeting described him as “a rather dry” orator who’s not a natural entertainer nor a tactile ‘Menschenfanger’ (catcher of men) like Jurgen Klopp. Unlike some of his predecessors at Bayer, he has shown little interest in club departments that don’t directly impact football. He only really cares about the game.

But that sort of single-mindedness has also inspired staff members at a club that has sometimes been mockingly described as a ‘Wohlfuhloase, an oasis of comfort, due to the relative lack of pressure to succeed. Alonso has managed to energise Leverkusen staffers with his professionalism, charm and hunger for success. “You just sort of believe every word he says, because of who he is and the way he says it,” the employee says. “You believe that he will bring success. Because he does.”

The players are similarly entranced. It doesn’t hurt that Alonso is still the best footballer on the training pitch six years into retirement. He regularly pings 50-metre diagonals that land on the intended blade of grass and plays vertical passes that cut through lines like a freshly sharpened yanagiba knife, all without breaking a drop of sweat.

Some people in the club were initially concerned his fantastic technique might intimidate the team, or worse, rub them the wrong way. They recalled 1990 World Cup winner Pierre Littbarski, in his role as assistant coach to Berti Vogts in Leverkusen in 2001, showing off his free-kick-taking skills, teasing the players for falling short of his standards. “You have to take out the shoe trees from your boots,” the former midfielder used to joke. Until one day, one Bayer player sought revenge — and ‘accidentally’ scythed down Littbarski in a training game.

That won’t happen to Alonso, and not just because he’s too slick to get caught by a mean-spirited tackle. The team respects and admires him far too much. “There are some former pros who try to impress players with their skills on the ball, since they don’t have much else to offer by way of coaching,” the senior club official says. “Xabi doesn’t need that. He just plays a killer pass to get his idea across — like somebody would draw an arrow on the tactics board — and to raise the quality of the training exercise.”

There’s an air of focus and commitment to the cause that hasn’t always been observed on the training pitches just across from the BayArena stadium. Alonso moves a lot, talks a lot and sometimes shouts if he feels that a specific message needs emphasis. Recently, he set his team a challenge to be more effective from set pieces. When they duly improved, he rewarded them with two days off.

“He’s a very clever man with sensitive antennas that pick up all sorts of signals,” says another Bayer source who works with Alonso on a daily basis. He points to the manager making sure that some players whose contributions are in danger of getting overlooked by the public receive their due share of the limelight and a bit of extra attention from him.

Alonso isn’t the sole reason for Bayer’s positive momentum, obviously. He has a strong relationship with Leverkusen’s Spanish CEO Fernando Carro and Rolfes, a former central midfielder who’s the same age as Alonso and shares many of his footballing convictions. His ideas are closely aligned with Leverkusen’s transfer policy, too.

The club’s scouting has been formidable for decades, but last summer they were especially smart. Selling French winger Moussa Diaby to Aston Villa for €60million (£52m, $63m) enabled them to invest in a couple more seasoned pros to complement the array of talented youngsters.

Former Arsenal midfielder Xhaka and Germany international Hofmann, both 31, have added character and mentality as much as quality to the dressing room. Grimaldo, 28, is also being mentioned as a hugely positive influence behind the scenes. And on top of that, it’s always useful to add a dynamic goalscorer in Boniface (six goals in five league games), signed for €20.5m from Union Saint-Gilloise.

Picking the right club to succeed is a coach’s most underrated skill. Alonso has been especially careful in that respect. He took this time to learn the trade in three years at Real Sociedad B and turned down a chance to coach Borussia Monchengladbach in the spring of 2021 — he knew from his time at Bayern as a player (2014-2017) that Leverkusen were a better fit.

Bayer are a relatively wealthy club committed to attacking football but they don’t operate in a cacophony of media noise, due to the small size of the city. It’s an ideal place for a young manager to make his next steps. The only question now is how long Bayer can keep up with a manager who’s going places.

Rolfes says they are not worried about reports linking Alonso to the Real Madrid job. “I never mind rumours about our players or coaches. If they’re good and successful, others will take note. In April, there were plenty of stories that Alonso would leave this summer. Didn’t happen.” Instead, he signed a new contract until 2026.

Bayer are not naive. If Alonso gets offered the Bernabeu job for next season and decides he’s ready to take it, the Germans won’t keep him against his will and will try to manage that process in a way that minimises disruption. But there’s still hope it won’t be over come May. Bayer have received no indication that Alonso wants to move on. And from everything they’ve seen so far, he’s not a man in a hurry.

(Top photo: Getty Images)